Por Ulises Carabantes Ahumada

Ingeniero Civil Industrial. Analista de actualidad. Escritor.

(At the end of the spanish text you will find the english translation)

Estimado lector, en las próximas líneas podrá leer un muy breve pero descriptivo resumen de algunos capítulos del libro Chile 1973. Quien quiera profundizar en esta materia y desee comprar el libro, consulte al correo ucarabantes@gmail.com, para las ediciones en Chile como también en España. Esta es la quinta de trece publicaciones sabatinas que efectuaré hasta el sábado 9 de septiembre.

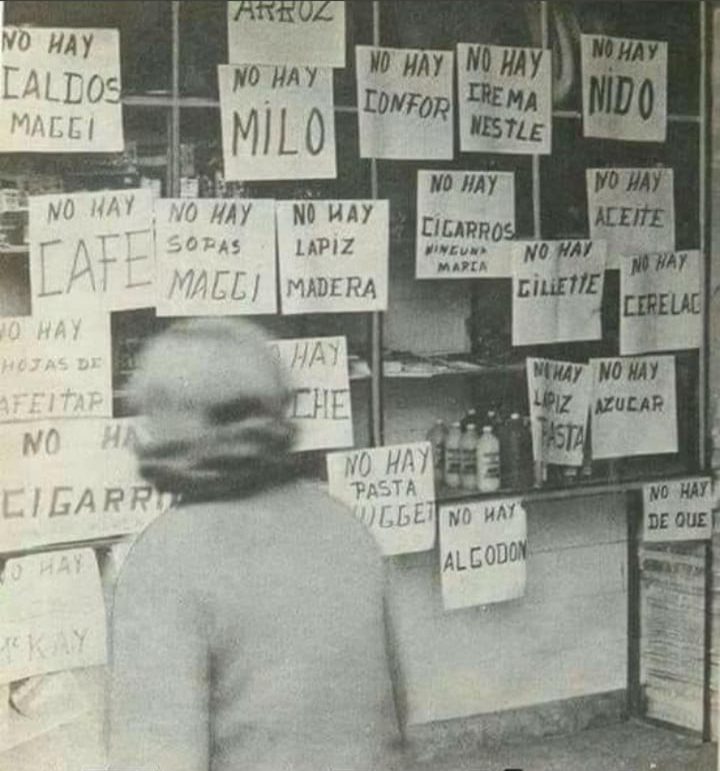

En medio de las tensiones provocadas por el proyecto educacional del gobierno denominado Escuela Nacional Unificada, ENU, el 19 de abril de 1973 se inició la huelga de los trabajadores de la mina de cobre El Teniente, movimiento gremial que tendría una larga duración y que, aún siendo focalizado en la Provincia de O´Higgins y Santiago, tuvo una gran repercusión política a nivel nacional y profundizando los quiebres internos que habían en la Unidad Popular. Durante mayo se produjeron violentos enfrentamientos en Santiago entre Patria y Libertad y grupos de izquierda, frente a lo cual el gobierno decretó el Estado de Emergencia. La pugna entre los poderes del Estado era evidente y permanente. La Cámara de Diputados acusó constitucionalmente al ministro de minería Sergio Bitar y al ministro del trabajo Luís Figueroa, por no dar solución y terminar con la huelga de los mineros de El Teniente. Nuevamente no hubo acuerdo entre el gobierno y el congreso en lo que se refería a definir legalmente las llamadas “áreas de la economía”. El tribunal constitucional se declaró sin competencia para resolver tal contienda, manteniéndose la situación de quedar la estructura productiva de Chile al arbitrio del gobierno o peor aún, bajo el arbitrio de agitadores de izquierda que paralizaban y tomaban fábricas y otras unidades de producción, lo que mantenía el desabastecimiento y el caos general en la economía.

Nuevamente no hubo acuerdo entre el gobierno y el congreso en lo que se refería a definir legalmente las llamadas “áreas de la economía”. El tribunal constitucional se declaró sin competencia para resolver tal contienda, manteniéndose la situación de quedar la estructura productiva de Chile al arbitrio del gobierno o peor aún, bajo el arbitrio de agitadores de izquierda que paralizaban y tomaban fábricas y otras unidades de producción, lo que mantenía el desabastecimiento y el caos general en la economía. Como se señaló anteriormente, por solicitud del presidente Salvador Allende, fuera de toda obligación constitucional, el general Carlos Prats inició la serie de reuniones de carácter político con los partidos de la Unidad Popular, buscando que estos aceptaran una tregua con la oposición, a fin de evitar el sangriento enfrentamiento fratricida y terminar la crisis que vivía Chile sin derramamiento de sangre. En paralelo, socialistas como el ex canciller Clodomiro Almeyda manifestaban, al igual que el presidente de la república, su visión de la necesidad de que las fuerzas armadas se incorporaran en labores de gobierno, pero el habitual interlocutor ante esta propuesta, como era Carlos Prats, manifestaba reiteradamente que para hacer factible nuevamente la incorporación de las fuerzas armadas a los ministerios, era necesario que el gobierno hiciera concesiones en su programa. Tanto Allende como Almeyda respondían muy poco probable que los partidos de la izquierda quisieran hacer dichas concesiones ante la oposición y Prats respondía que en ese caso no era factible la incorporación militar al gobierno pues aparecerían las fuerzas armadas tomando posición por uno de los bandos en pugna.

Como se señaló anteriormente, por solicitud del presidente Salvador Allende, fuera de toda obligación constitucional, el general Carlos Prats inició la serie de reuniones de carácter político con los partidos de la Unidad Popular, buscando que estos aceptaran una tregua con la oposición, a fin de evitar el sangriento enfrentamiento fratricida y terminar la crisis que vivía Chile sin derramamiento de sangre. En paralelo, socialistas como el ex canciller Clodomiro Almeyda manifestaban, al igual que el presidente de la república, su visión de la necesidad de que las fuerzas armadas se incorporaran en labores de gobierno, pero el habitual interlocutor ante esta propuesta, como era Carlos Prats, manifestaba reiteradamente que para hacer factible nuevamente la incorporación de las fuerzas armadas a los ministerios, era necesario que el gobierno hiciera concesiones en su programa. Tanto Allende como Almeyda respondían muy poco probable que los partidos de la izquierda quisieran hacer dichas concesiones ante la oposición y Prats respondía que en ese caso no era factible la incorporación militar al gobierno pues aparecerían las fuerzas armadas tomando posición por uno de los bandos en pugna.

El 7 de junio de 1973 el general Carlos Prats comenzó a desarrollar la misión política que se le había solicitado. Ese día se reunió con la dirigencia de la Central Única de Trabajadores, CUT, encabezada por el comunista Luís Figueroa y el socialista Rolando Calderón, quienes transparentaron su visión de fortalecer al gobierno con la incorporación definitiva a éste de las fuerzas armadas y de esta forma actuar con mayor fuerza frente a la oposición para combatir la inflación y el desabastecimiento. Carlos Prats les respondió lo obvio, la inflación y el desabastecimiento se combatía entregando la unidades productivas, fábricas y campos, a quienes las sabían hacer producir, dejando de estar en manos de los agitadores políticos de la Unidad Popular y del MIR, quienes tenían paralizadas dichas unidades productivas, sometiéndolas a interminables y estériles asambleísmos. El mismo 7 de junio se reunió Carlos Prats con la dirigencia del partido socialista, con el secretario general de este partido, Carlos Altamirano, en presencia de carlos Lazo, Hernán del Canto, Rolando Calderón y Adonis Sepúlveda, el mismo que en 1965 levantó al tesis insurreccional aprobada por los socialistas en su congreso general de junio de ese año. Carlos Altamirano fue muy claro con Prats, expuso la visión de su partido, que distaba enormemente de la visión que el presidente Allende le había manifestado al mismo general, la que era lograr un acuerdo con la oposición a través de concesiones programáticas por parte de la Unidad Popular, para así establecer una tregua política que alejara el lúgubre fantasma de una guerra civil. Altamirano expresó a Prats que los socialistas no estaban por hacer concesiones de ningún tipo a la oposición, es decir, no eran partidarios de dar el paso que permitiera a Allende salvar su gobierno. Muy por el contrario, Altamirano le señaló al general Carlos Prats que las fuerzas armadas debían ponerse del lado “del pueblo”, entendiéndose como “el pueblo” al sector que había obtenido el 43% de los sufragios en las elecciones parlamentarias de marzo de 1973; es decir, a los seguidores de la Unidad Popular. Si el socialista Carlos Altamirano consideraba legítima la intervención de las fuerzas armadas a favor “del pueblo” del 43%; ¿por qué no podía ser legítima una intervención de las fuerzas armadas a favor del pueblo que tenía el mayoritario 57%? En resumen, Carlos Altamirano estaba proponiendo el definitivo quiebre democrático para Chile, por tres caminos, una dictadura marxista apoyada por las fuerzas armadas o una dictadura anti marxista apoyada también por las fuerzas armadas o sencillamente la guerra civil si las fuerzas armadas intervenían militarmente en forma dividida.

El mismo 7 de junio se reunió Carlos Prats con la dirigencia del partido socialista, con el secretario general de este partido, Carlos Altamirano, en presencia de carlos Lazo, Hernán del Canto, Rolando Calderón y Adonis Sepúlveda, el mismo que en 1965 levantó al tesis insurreccional aprobada por los socialistas en su congreso general de junio de ese año. Carlos Altamirano fue muy claro con Prats, expuso la visión de su partido, que distaba enormemente de la visión que el presidente Allende le había manifestado al mismo general, la que era lograr un acuerdo con la oposición a través de concesiones programáticas por parte de la Unidad Popular, para así establecer una tregua política que alejara el lúgubre fantasma de una guerra civil. Altamirano expresó a Prats que los socialistas no estaban por hacer concesiones de ningún tipo a la oposición, es decir, no eran partidarios de dar el paso que permitiera a Allende salvar su gobierno. Muy por el contrario, Altamirano le señaló al general Carlos Prats que las fuerzas armadas debían ponerse del lado “del pueblo”, entendiéndose como “el pueblo” al sector que había obtenido el 43% de los sufragios en las elecciones parlamentarias de marzo de 1973; es decir, a los seguidores de la Unidad Popular. Si el socialista Carlos Altamirano consideraba legítima la intervención de las fuerzas armadas a favor “del pueblo” del 43%; ¿por qué no podía ser legítima una intervención de las fuerzas armadas a favor del pueblo que tenía el mayoritario 57%? En resumen, Carlos Altamirano estaba proponiendo el definitivo quiebre democrático para Chile, por tres caminos, una dictadura marxista apoyada por las fuerzas armadas o una dictadura anti marxista apoyada también por las fuerzas armadas o sencillamente la guerra civil si las fuerzas armadas intervenían militarmente en forma dividida.

En la tarde del 8 de junio de 1973 el general Carlos Prats se reunió con los dirigentes del MAPU Enrique Correa, Jaime Gazmuri y Fernando Flores. Tras repetir su planteamiento de la urgente necesidad de un acuerdo con la oposición, Carlos Prats recibió como respuesta de estos tres políticos su incredulidad respecto de que fuera factible la aceptación de la tregua por el sector mas derechista de la democracia cristiana, como así también por parte de los sectores más radicalizados hacia la izquierda de la Unidad Popular. A esta visión del MAPU habría que agregar también la permanente presión del MIR sobre el gobierno, en su afán revolucionario violentista que ponía en práctica el “avanzar sin tranzar” que vociferaba. El mismo 8 de junio por la noche el general Carlos Prats se reunió con los dirigentes comunistas Luís Corvalán, Volodia Teitelboim, Orlando Millas y Hugo Díaz. Los comunistas se expresaron contrarios a un acuerdo con la oposición argumentando que aquello desorientaría y debilitaría las bases partidarias de la Unidad Popular. En consecuencia, los comunistas tampoco se motraron de acuerdo con la tregua política que pedía el presidente Salvador Allende, cerraban la puerta a la posibilidad de un acuerdo con la oposición para impedir el golpe militar que con franqueza les anunciaba el comandante en jefe del ejército Carlos Prats. Habría que haberle preguntado a los testarudos líderes de la UP, ¿qué debilitaría más a las bases partidarias de su coalición, un acuerdo con la oposición o una intervención militar como la que ocurriría el 11 de septiembre de 1973?

El comandante en jefe del ejército transmitió el fracaso que estaba teniendo en su gestión política a su subalterno más directo, el jefe de estado mayor del ejército, general de división Augusto Pinochet. Este manifestó su visión ante Prats en el sentido de que la crisis que vivía Chile debía tener una solución de carácter político, sin dejar de expresar una alerta, la posibilidad que la oficialidad del ejército exigiera un pronunciamiento de la institución ante la grave crisis que se vivía. Veinte días después vino el “tancazo”, ya referido en esta serie de publicaciones.

En consecuencia Prats fracasó en su intento político de bajar la intensidad de enfrentamiento de los dos bandos en pugna, enfrentamiento que era condición fundamental para que Chile cayera en una guerra civil. Esta última se concretaría definitivamente con una intervención militar fraccionada, dividida, a favor de uno y otro bando, como lo esperaban en su diseño el frente nacionalista patria y libertad y por el lado de la izquierda, el partido comunista, el partido socialista y el MIR. Desde ese momento en adelante sólo esperaba a Chile la guerra civil o que los altos mandos de las fuerzas armadas lograran ejecutar una intervención militar monolítica, unida, para terminar con el caos generalizado imperante. Dicha intervención se produjo el 11 de septiembre de 1973.

La tarde del 15 de junio hubo violentos enfrentamientos en la zona céntrica de Santiago, en el contexto de la huelga de los trabajadores de la mina El Teniente. El senador demócrata cristiano llamó por teléfono al general Prats señalándole temer un ataque a la sede de su partido, que carabineros estaba sobrepasado y que el comunista Luís Figueroa, presidente de la CUT y el socialista Jorge Arrate, vicepresidente de CODELCO, pretendían bloquear el acuerdo que el presidente Allende intentaba con los huelguistas.

Al día siguiente fueron ratificados los dichos de Aylwin respecto de Luís Figueroa y Jorge Arrate, pues la comisión política del partido comunista y la comisión política del partido socialista emitieron una dura crítica al presidente Salvador Allende a través del diario comunista El Siglo, declaración en la cual ambos partidos señalaron que el diálogo con los dirigentes mineros que carecían de representatividad era inconducente y que sólo la combatividad de las masas (comunistas y socialistas) era válida para dar término al problema. Allende tuvo que dar explicaciones públicas a ambos partidos de izquierda.

En paralelo, Carlos Prats veía aumentar la desconfianza hacia su liderazgo dentro del cuerpo de generales del ejército. Posterior al “tancazo” el alto amndo de la armada solicitó una reunión conjunta con generales del ejército y la fuerza aérea con el fin de “orientarse de la situación que se vive y uniformar criterios”.

Si durante las trece publicaciones de este ciclo histórico, alguno de mis lectores se interesa en tener el libro Chile 1973; tanto para la edición en Chile como en España, pueden hacer llegar su consulta al correo electrónico ucarabantes@gmail.com

Los espero el próximo sábado 22 de julio con la sexta publicación histórica, la que llevará por título Cincuenta Años: Inclinación por la Violencia.

Fifty Years

Tensions and Distrust

By Ulises Carabantes Ahumada

Industrial Civil Engineer. Current Affairs Analyst. Writer.

Dear reader, in the following lines, you will be able to read a very brief but descriptive summary of some chapters from the book ‘Chile 1973’. For those who wish to delve deeper into this matter and want to purchase the book, please contact ucarabantes@gmail.com for editions available in Chile and Spain. This is the fifth out of thirteen Saturday publications that I will be releasing until Saturday, September 9th.

Amidst the tensions caused by the government’s educational project called the National Unified School, ENU, the strike of workers at the El Teniente copper mine began on April 19, 1973. This labor movement had a long duration and, even though it was focused mainly in the O’Higgins Province and Santiago, it had a significant political impact nationwide, deepening the internal ruptures within the Popular Unity. Violent clashes occurred in Santiago in May between Patria y Libertad (homeland and freedom) and left-wing groups, prompting the government to declare a state of emergency. The power struggle between the branches of the State was evident and constant. The Chamber of Deputies constitutionally accused the Minister of Mining, Sergio Bitar, and the Minister of Labor, Luís Figueroa, for failing to provide a solution and end the strike of the El Teniente miners.

Once again, no agreement was reached between the government and the Congress regarding the legal definition of the so-called ‘economic areas.’ The Constitutional Court declared itself incompetent to resolve this dispute, thus maintaining the situation where Chile’s productive structure was left to the government’s discretion or worse, to the discretion of left-wing agitators who were causing work stoppages and taking over factories and other production units, resulting in shortages and general chaos in the economy.

As previously mentioned, at the request of President Salvador Allende, outside of any constitutional obligation, General Carlos Prats initiated a series of political meetings with the parties of the Popular Unity. The goal was to persuade them to accept a truce with the opposition in order to avoid a bloody fratricidal confrontation and end the crisis in Chile without bloodshed. In parallel, socialists like former Foreign Minister Clodomiro Almeyda expressed, just like the President, their view of the need for the armed forces to be involved in governmental tasks. However, the usual interlocutor for this proposal, Carlos Prats, repeatedly stated that for the reintegration of the armed forces into the ministries to be feasible, the government needed to make concessions in its program. Both Allende and Almeyda responded that it was highly unlikely that leftist parties would be willing to make such concessions to the opposition. Prats replied that in that case, the military’s incorporation into the government would not be feasible, as it would appear that the armed forces were taking sides in the conflict.

On June 7, 1973, General Carlos Prats began to carry out the political mission he had been assigned. That day, he met with the leadership of the Central Única de Trabajadores (Unified Workers’ Central), CUT, led by the communist Luis Figueroa and the socialist Rolando Calderón. They expressed their vision of strengthening the government by definitively incorporating the armed forces into it, thereby acting more forcefully against the opposition to combat inflation and shortages. Carlos Prats pointed out the obvious to them: inflation and shortages could be combated by handing over productive units, factories, and fields to those who knew how to make them productive, rather than being in the hands of political agitators from the Popular Unity and the MIR, who had paralyzed these productive units, subjecting them to endless and fruitless assemblies.

On the same day, Carlos Prats met with the leadership of the Socialist Party, including its General Secretary Carlos Altamirano, in the presence of Carlos Lazo, Hernán del Canto, Rolando Calderón, and Adonis Sepúlveda. It is worth noting that Adonis Sepúlveda was the same person who in 1965 proposed the insurrectional thesis approved by the socialists at their general congress that same year. Carlos Altamirano was very clear with Prats, expressing his party’s vision, which greatly differed from the vision President Allende had conveyed to the general. Altamirano’s vision was to achieve an agreement with the opposition through programmatic concessions from the Popular Unity, in order to establish a political truce that would dispel the gloomy specter of a civil war. Altamirano told Prats that the socialists were not inclined to make any concessions to the opposition, meaning they were not in favor of taking the step that would allow Allende to save his government. On the contrary, Altamirano told General Carlos Prats that the armed forces should stand on the side of «the people,» understanding «the people» as the sector that had obtained 43% of the votes in the parliamentary elections of March 1973, in other words, the followers of the Popular Unity. If the socialist Carlos Altamirano considered the intervention of the armed forces on behalf of the 43% «people» legitimate, why couldn’t an intervention of the armed forces on behalf of the majority 57% «people» also be legitimate? In summary, Carlos Altamirano was proposing the definitive democratic rupture for Chile through three paths: a Marxist dictatorship supported by the armed forces, an anti-Marxist dictatorship also supported by the armed forces, or simply civil war if the armed forces intervened militarily in a divided manner.

On the afternoon of June 8, 1973, General Carlos Prats met with the leaders of the MAPU party, Enrique Correa, Jaime Gazmuri, and Fernando Flores. After reiterating the urgent need for an agreement with the opposition, Carlos Prats received disbelief from these three politicians regarding the feasibility of the right-wing sector of the Christian Democracy accepting a ceasefire, as well as the more radicalized sectors of the Left of the Popular Unity. This view from the MAPU also had to take into account the constant pressure from the MIR on the government, with their revolutionary and violent approach of «advancing without compromise.»

Later that same evening of June 8, General Carlos Prats met with Communist leaders Luís Corvalán, Volodia Teitelboim, Orlando Millas, and Hugo Díaz. The Communists expressed their opposition to an agreement with the opposition, arguing that it would disorient and weaken the party bases of the Popular Unity. Consequently, the Communists were also not in agreement with the political truce requested by President Salvador Allende. They closed the door to the possibility of an agreement with the opposition to prevent the military coup that the Army Commander-in-Chief, Carlos Prats, frankly announced to them. One might have asked the stubborn leaders of the Popular Unity, what would weaken the party bases of their coalition more: an agreement with the opposition or a military intervention like the one that would occur on September 11, 1973?

The Army Commander-in-Chief conveyed his political failure to his direct subordinate, the Army Chief of Staff, Major General Augusto Pinochet. Pinochet expressed his view to Prats that the crisis affecting Chile needed a political solution, while also raising the possibility that the army’s officers might demand an institutional pronouncement regarding the grave crisis being experienced. Twenty days later came the «tancazo,» already referred to in this series of publications.

As a result, Prats failed in his political attempt to reduce the intensity of the confrontation between the two warring sides, a confrontation that was a fundamental condition for Chile to fall into a civil war. This civil war would ultimately materialize with a fractured and divided military intervention, supporting one side or the other, as anticipated in their design by the nationalist «Patria y Libertad» front and, on the left, the Communist Party, the Socialist Party, and the MIR. From that moment onwards, Chile could only expect either a civil war or the high-ranking commanders of the armed forces executing a unified military intervention to end the prevailing generalized chaos. Such an intervention took place on September 11, 1973.

On the afternoon of June 15, violent clashes occurred in the downtown area of Santiago, in the context of the strike by El Teniente mine workers. A Christian Democrat senator phoned General Prats, expressing concern about an attack on his party’s headquarters, stating that the police were overwhelmed and that Communist leader Luís Figueroa, President of the CUT (Central Unitaria de Trabajadores), and Socialist Jorge Arrate, Vice President of CODELCO, intended to block the agreement that President Allende was attempting to reach with the striking workers.

The following day, the statements made by Aylwin regarding Luís Figueroa and Jorge Arrate were confirmed, as both the Communist Party’s political commission and the Socialist Party’s political commission issued a harsh critique of President Salvador Allende through the Communist newspaper El Siglo. In that declaration, both parties stated that dialogue with the non-representative mining leaders was futile and that only the combativeness of the masses (Communists and Socialists) was valid in ending the problem. Allende had to provide public explanations to both left-wing parties.

Meanwhile, Carlos Prats saw the distrust towards his leadership increase within the ranks of the Army generals. After the «tancazo,» the high command of the Navy requested a joint meeting with Army and Air Force generals in order to «assess the situation being experienced and unify criteria.»

If, during the thirteen publications of this historical series, any of my readers are interested in obtaining the book Chile 1973, both for the edition in Chile and Spain, they can send their inquiries to the email address ucarabantes@gmail.com.

I will see you next Saturday, July 22, with the sixth historical publication, which will be titled «Fifty Years: Inclination towards Violence.»